Living Image (2017)

Living Image (2017)

I was delighted to be asked to be the juror for The Halide Project’s exhibition, Living Image 2017 at Gravy Studio & Gallery, which for me has been a wonderful introduction to the exciting work being done by this organization. Beyond this annual juried exhibition, The Halide Project organizes workshops, exhibitions, and a community darkroom, which explore and promote the artistic use of traditional and alternative photographic processes. Their mission, while specific, encompasses a broad array of photographic processes, some of which are still somewhat commonly used, for example, capturing images using film or the making of black and white silver prints in a darkroom. Works utilizing both of these methods are included here. But a large number of the works submitted were made using other, much less commonly known processes, for example, gum bichromate prints and wet plate collodion. One significant thing to note is that all of the prints included in this grouping relied on reactions between chemicals and light in the production of the image, rather than being formed from ink being applied to paper.

Submissions to Living Image came through an international open call, which invited artists to submit any work created using traditional or alternative photographic processes. The submitted works are notable for their differences in purpose, technical origin, genre, and personality, but overall the entries showed a serious commitment to experimentation and a critical engagement in the acts of seeing and understanding. I would like to thank Frank C. Barbella and Susan Stromquist from The Halide Project for their invitation to jury this exhibition, as well as their attention and assistance during its organization.

For the selection process, I looked at all of the entries twice, the first time quickly just to get a sense of what I was working with. I then made a second, much slower pass. Several times I spent at least a minute or two on one work just trying to decipher what I was looking at. I did not set out to impose a tight agenda on what I selected, embracing the idea that this exhibition would highlight the diversity of work being made using these processes rather than trying to create a rigidly cohesive grouping.

In general, most contemporary photography is more concerned with the image of the photograph than the object that is the print. The work of many of today’s photographers seems to exist just as happily in the virtual world as in the actual world. Overwhelmingly, artists who are working in photography today are making inkjet prints of images that were digitally captured. Perhaps because of the capabilities of inkjet printers today, prints by many contemporary photographers are relatively large, slickly produced, and exquisitely detailed. While the resulting works can be breathtakingly beautiful, this widespread approach can also come across as coolly mechanical, with little critical link between the image of the work, the process by which it was made, and the resulting print.

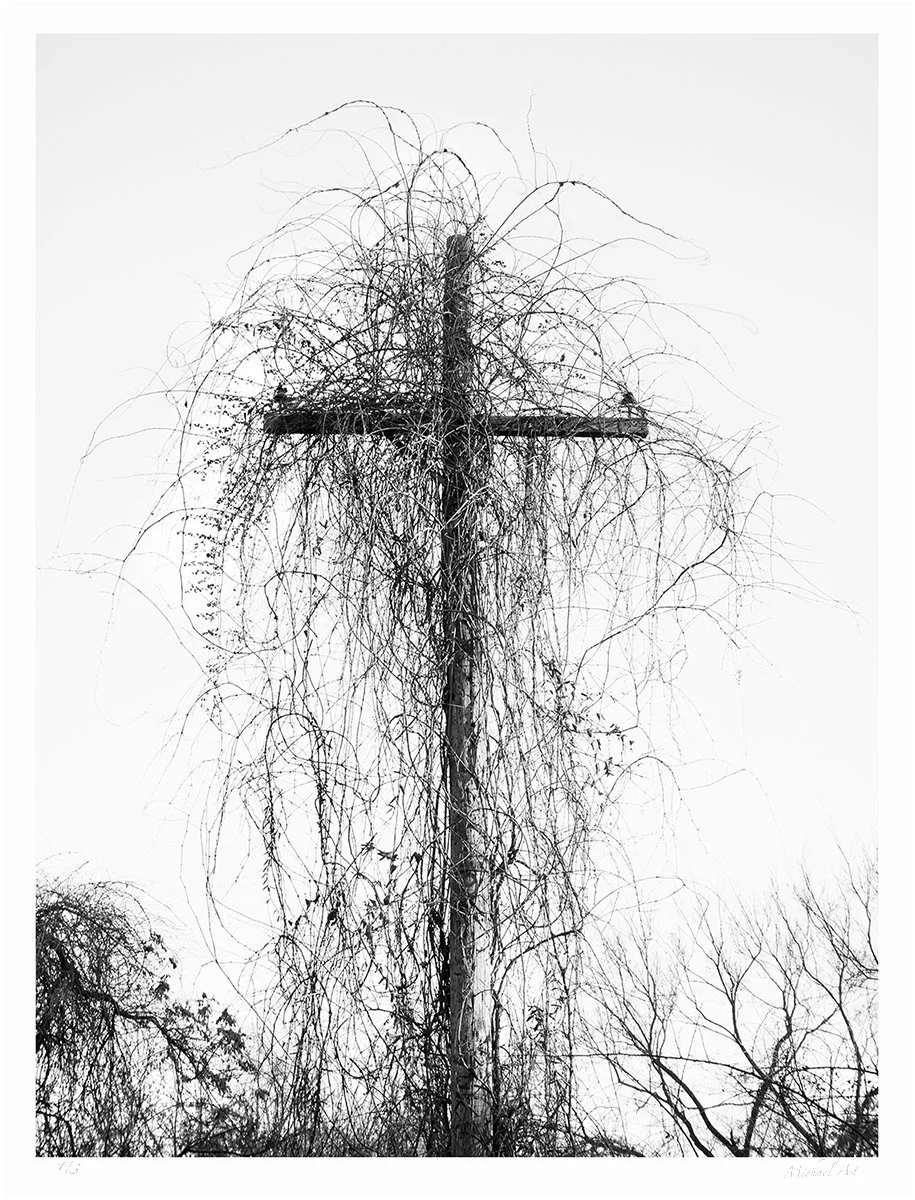

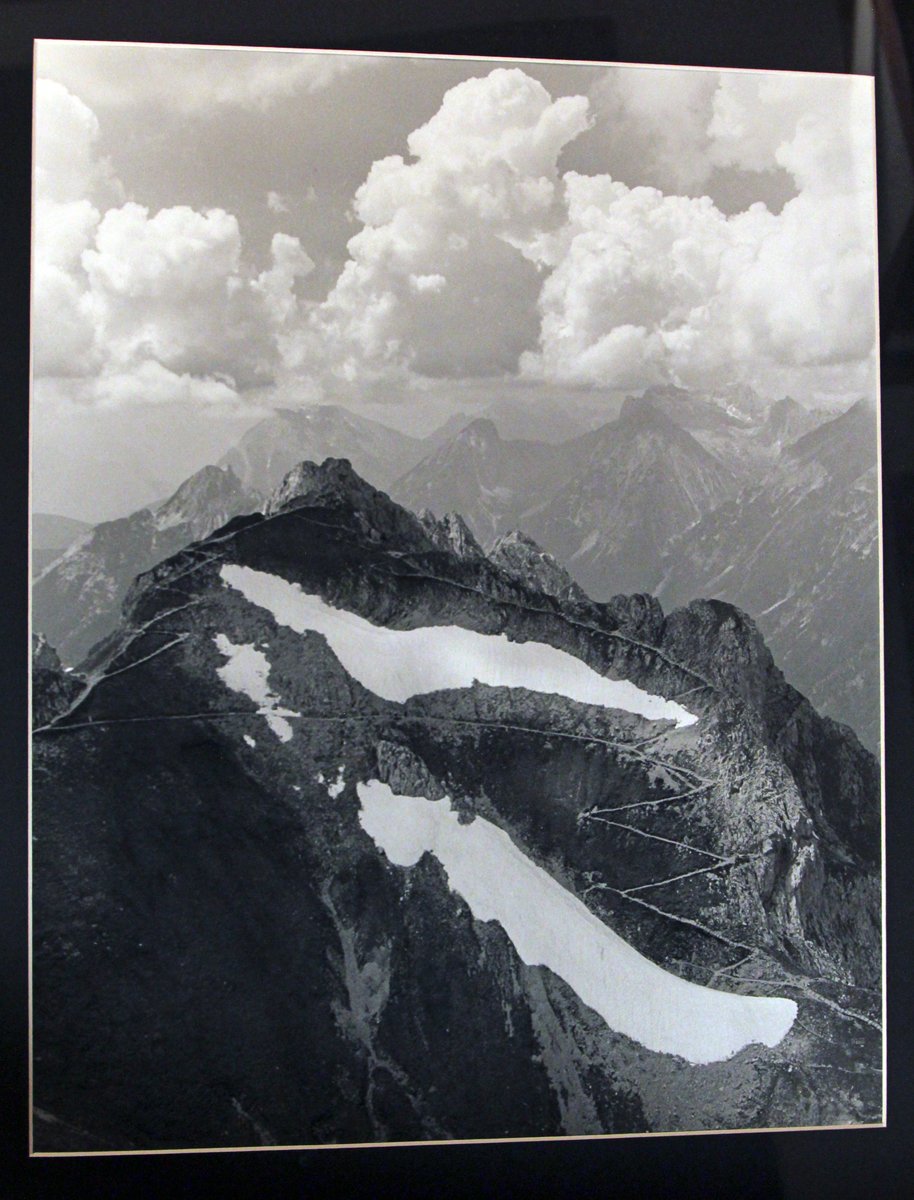

The array of works included in this exhibition could not be further from this widespread trend. Each of the artists here has elected to use processes of capturing images and making photographic prints that are old-fashioned, technically difficult, fickle, often dangerous, and expensive. Despite making their lives as artists difficult, or perhaps because of it, they have found an amazing wealth of opportunities for exploration and experimentation.

While this collection of works is not tightly curated, there are a few sub-themes that pop out to me. First, I was struck by how many artists were drawn to processes that lent themselves to the creation of photographs that combined passages of almost hallucinatory detail, with shifts to obscurity that verged on obliterating the image, for example, Amanda Tinker’s constructed, surreal scenarios. Denise Ross’ radiant portrait of a glowing bunch of turnips recalls the 19th century photographer Charles Jones’ photographs of produce. Meanwhile, in Cora Cluett’s images of sugar bowls, the marks on the vessels begin to become more tangible than the vessels themselves, which seem to be dissolving into the air.

Improvisation in both the making of the image and the making of the print was another theme that came up. Shaina Nyman’s photograph of a woman who appears to be sitting and squatting simultaneously is an example of an artist working against the conventions of a static, controlled photographic image. Meanwhile, Iryna Glik’s cyanotypes are dominated by the bold brushstrokes she used to apply her chemistry to the paper in the making of the print itself. Also, a number of artists choose subjects that are stubbornly eccentric, for example, John Jackson’s image of a grouping of rocks forming an almost human-like shape and Bob Carnie’s almost mysterious portrait of a lumpy, wizened turnip. Anne Eder’s view through a complex series of architectural spaces to a tiny dog also captures this spirit of creating images of everyday scenes and objects, which become unexpectedly personal and idiosyncratic photographs.

Finally, I loved seeing so much work where the artist seemed to revel in the science of the creation of the image, not unlike a chemist in a laboratory. Lucang Huang’s silver print made from sea water reminds us of how many diverse ways a photograph can be made. Meanwhile, in Angela Franks Wells’ picture of a plant’s branch, the chemistry used to create the image seems to be erupting on the surface of the print, making her work seem almost alchemical.

All of the works in Living Image play a critical role in communicating the multi-faceted and ever-changing importance of traditional and alternative process photography.